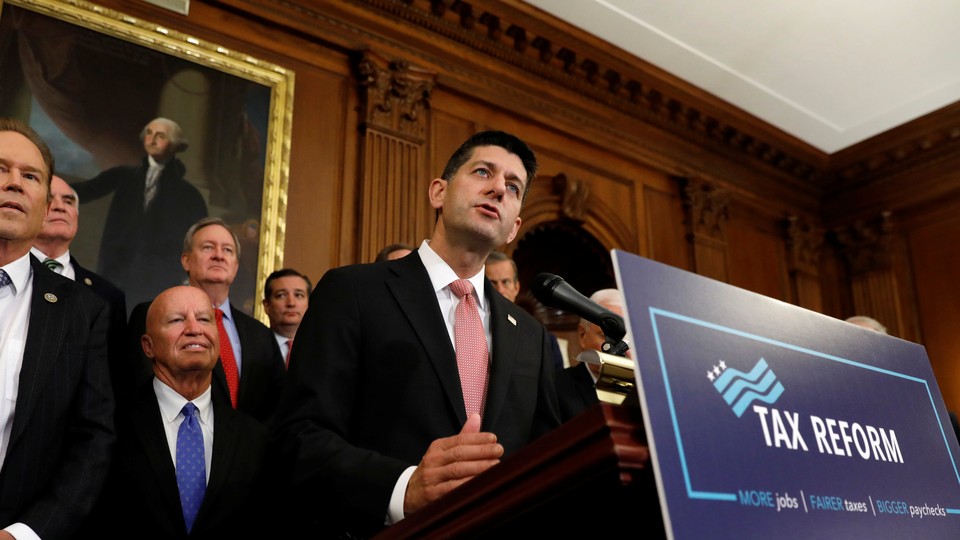

The Original Sin of the GOP Tax Plan

How did a proposal to simplify the tax code become such a mess? Blame its first principles.

The new tax bill released by the House GOP on Thursday would permanently slash the corporate tax rate from 35 percent to 20 percent, reduce the number of individual income tax brackets, and repeal a host of taxes paid by the richest households, including those inheriting estates worth millions of dollars.

So far, it sounds like the most predictable Republican plan imaginable.

But anybody who heard House Speaker Paul Ryan’s repeated promises to cut taxes and simplify the tax code might be surprised that, for millions of people making less than $100,000, taxes would go up, and for many small businesses, filing would be more complicated. Perhaps most importantly, the plan adds trillions in debt over 20 years, making it nearly useless as a blueprint for the Senate. That’s because the Senate will likely try to pass the bill under a procedure known as reconciliation, which requires only a simple majority of votes but prohibits any law from adding at all to deficits after 10 years.

“This is not what I would call a tax-simplification plan,” said Howard Gleckman, an economist at the nonpartisan Tax Policy Center. “It raises taxes idiosyncratically on large families in rich states. And it makes life hard for some of the very small businesses it’s trying to help.”

As an example, Gleckman points to the plan’s treatment of what are called “pass-through” taxes paid by small businesses. The GOP plan lowers the rate for these taxes, but includes several rules to prevent rich individuals from classifying themselves as dummy companies in order to pay less in taxes thanks to the new rate. Gleckman worries that these anti-abuse measures will backfire: Rich people will just hire smart lawyers to handle all the new paperwork, while the maze of caveats will make life hell for small businesses. Indeed, the National Federation of Independent Business, the lobby for the nation's small businesses, said on Thursday that it was “unable to support” the bill as released, due to concerns about the pass-through provisions.

How did a plan to simplify the tax code become such a mess? Blame the first principles of the proposal.

Before the last major tax reform in 1986, Ronald Reagan’s Treasury Department set out to pass an economically rational, deficit-neutral, bipartisan bill. The modern Republican Party, however, is starting from a principle that isn’t bipartisan, deficit-neutral, or economically rational at all: that, with corporate profits and the stock market at all-time highs, America’s largest corporations deserve a $2 trillion tax cut.

“This is the tax plan’s original sin,” said Michael Linden, an economist at the left-leaning Roosevelt Institute. “Once you cut the tax rate for large corporations by more than a third, you have to cut tax rates for smaller businesses so that they don’t feel disadvantaged.”

But those two measures alone cost more than $2.5 trillion over the course of 10 years, which is too much to appease deficit-hawk Republicans. So the authors had to gin up government revenue elsewhere to compensate. That explains the proposed repeal of some popular and virtuous benefits, like the tax credit for adopting children and deductions for student-loan interest and medical expenses.

“Why would you want to raise the bottom tax rate from 10 percent to 12 percent? Why would you want to make it harder to deduct medical expenses? Well, you have to make these choices if you start from the premise that the business community deserves a nearly $3 trillion tax cut,” Linden said. The insistence on slashing corporate tax rates is driven not only by a corporate donor class expecting a business stimulus from Republicans but also by an intellectual inertia that has set in, beginning in the early Reagan years. This is the dictum that lower tax rates are a panacea for all economic problems and even necessary when (as anybody can see from this stock market) there aren’t many problems in the first place.

The Republican tax plan does have a few things going for it. For example, it makes sports stadiums ineligible for tax-exempt bonds and moderately increases the child tax credit. Also, braving the ire of lobbyists, the authors of the bill also kill some sacred cows. For example, the law caps the mortgage-interest deduction at $500,000 of debt and caps the state and local tax deduction.

But, curiously, it’s mostly tax benefits for upper-middle-income earners that are slated for repeal. The rich are spared. For example, the infamous carried-interest loophole, which is a boon for those working in the private-equity industry, would be preserved, while the Alternative Minimum Tax (which cost Donald Trump $31 million in 2005) would be eliminated. The estate tax, which applies to the inheritance of estates worth more than $5 million, would be phased out and then permanently junked.

And while the plan creates a new tax bracket for all earned income over $1 million, every million-dollar earner would still be guaranteed a tax cut. That’s because the second-highest tax rate, on income between $400,000 and $1 million (which, by definition, includes income earned by every million-dollar household), would be cut by about five percentage points. Somebody earning $2 million a year could save about $30,000 on taxes from this change alone.

But again, it is all about first principles. Tax cuts for the rich and America’s largest corporations take up so much space in the bill that there’s little room to help poor and middle-class families. So if the plan looks messy, that’s only because finding a way to pass a $2.5 trillion corporate tax cut on a party-line vote is, well, a mess.